The premise

In React there are three different ways to define components. The simpler ones can be pure functions, while the rest can be expressed either as ES6 classes inheriting from React.Component, or as calls to React.createClass. The official React docs make it very clear that ES6 classes is the recommended way, by introducing React.createClass under the demeaning headline React without ES6.

In other words, if you don't have a transpiler in your build step, use React.createClass, otherwise use ES6 classes. But I personally prefer React.createClass over ES6 classes even though I use all other ES6 bells and whistles!

In this post I'll go over my main gripes about ES6 classes:

- Inconsistent context

- No mixin support

- Inconsistent state handling

- Inconsistent definition

- Dealing with

super

Most of this has been covered to death in the-difference-between-ES6-classes-and-createClass style posts, but here I'll focus on why I feel that the ES6 class syntax is inferior to React.createClass.

1) Inconsistent context

The most common caveat to run into is likely that with ES6 classes, methods aren't autobound to the instance. Which means that for the buyMoreBeer clickhandler below to work...

class Fridge extends React.Component {

buyMoreBeer() {

this.setState({beer: this.state.beer + 1});

}

// rest redacted

}...we have to fix the context ourselves, like a well-behaved dog. Either by setting it in the class constructor...

constructor() {

super();

this.buyMoreBeer = this.buyMoreBeer.bind(this);

}...or handling it in the render event hookup:

render() {

return (

<button onClick={(e)=> this.buyMoreBeer(e)}>Get more</button>

)

}Of course, in the heat of battle, it is very easy to forget this. And while the explanations as to why are perfectly understandable, the fact that this code...

class PeepingAtThis extends React.Component {

constructor() {

super();

console.log("Constructor",this instanceof React.Component);

}

componentDidMount() {

console.log("componentDidMount",this instanceof React.Component);

}

handleClick() {

console.log("handleClick",this instanceof React.Component);

}

render() {

console.log("Render",this instanceof React.Component);

return <button onClick={this.handleClick}>Click!</button>;

}

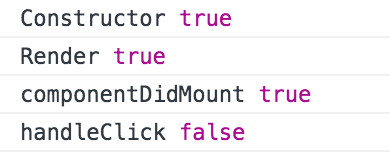

}...yields this output...

...just isn't very elegant.

The React docs themselves say that

This means writing ES6 classes comes with a little more boilerplate code for event handlers, but the upside is slightly better performance in large applications.

Maybe I'm being naïve, but surely that slight performance benefit only matters in a few edge-case applications, meaning the boilerplate-for-speed trade is a loss for everyone else?

2) No mixin support

The venerable React.createClass helper has a mixins API which lets us share objects of predefined functionality between components. Commonly a mixin will be provided by a 3rd party library to help interaction with React, such as the ReactFireMixin to connect a React component to Firebase.

React.createClass({

mixins: [ReactFireMixin],

// rest redacted

})The reason for having a special API and not just simply mix objects together is that both the mixin and the component might need to define the same lifecycle methods, in which case the mixin API will take care of wrapping those and making things work.

However, ES6 classes cannot use mixins. Which in many cases means that you're out of luck, have to dig under the hood of the mixin and recreate the functionality yourself.

Or the mixin author might have made a new version in the form of a class instead, like React themselves did with the PureRenderMixin which implements a good default for shouldComponentUpdate. This mixin is now instead available as a PureComponent base class:

class WhatAmI extends React.PureComponent {

render() {

console.log("Is pure", this instanceof React.PureComponent)

console.log("Is component", this instanceof React.Component)

return <div>Just testing</div>;

}

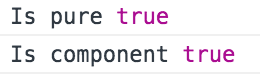

}...which of course in turn inherits from React.Component:

But, to my mind, inheritance is a vastly inferior model. Let's say that there was now a base class version of ReactFireMixin (which there isn't). How would you go about using that and PureComponent at the same time? You can't! While with React.createClass, no problem:

React.createClass({

mixins: [ReactFireMixin,PureRenderMixin],

// rest redacted

})Yes, I'm aware that mixins as a pattern aren't all that useful and can even be harmful. But I would argue that there are situations where they make sense, and in those situations they blow base classes out of the water.

3) Inconsistent state handling

In old React code there is an easy adage to live by regarding state:

Never ever mutate

this.statedirectly!

We provide inital state through the getInitialState method, and setState calls cause subsequent updates. We can use this.state.someKey to query our state, but we will never ever mutate this.state directly.

ES6 classes break this because reasons. Now we provide initial state by assigning it inside the constructor instead:

constructor(){

super();

this.state = {beer: 3};

}...giving us a far less elegant adage:

Never ever mutate

this.statedirectly! ...except for in the constructor.

4) Inconsistent definition

React.createClass is called with a single definition object. Many keys in that object will have some special meaning to React, while some will just be event handlers. Together they make up the entire class definition, in what is in my mind a very coherent way.

The ES6 classes are far less consistent. Most of the definition object keys end up as corresponding keys in the class definition, but not all! Some wind up inside the constructor, and some as props on the class object, because reasons.

Here is a simple definition object where each key is annotated with where they would end up in an ES6 version:

let Fridge = React.createClass({

propTypes: { // class object property

brand: React.PropTypes.string

},

defaultProps: { // class object property

brand: "beer"

},

getInitialState(){ // inside constructor

return {count:3};

},

componentWillMount(){ // inside constructor OR class definition key

console.log("Plugging in fridge");

},

buyMoreBeer(){ // class definition key

this.setState({count: this.state.count+1});

},

render() { // class definition key

return (

<div>

<p>{this.state.count} bottles of {this.props.brand} on the wall!</p>

<button onClick={this.buyMore}>Buy more</button>

</div>

);

}

})Translated to an ES6 class, here's what we get:

class Fridge extends React.Component {

constructor(){

super();

console.log("Plugging in fridge");

this.state = {count:3};

}

buyMoreBeer(){

this.setState({count: this.state.count+1});

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<p>{this.state.count} bottles of {this.props.brand} on the wall!</p>

<button onClick={this.buyMore}>Buy more</button>

</div>

);

}

}

Fridge.propTypes = {

brand: React.PropTypes.string

};

Fridge.defaultProps = {

brand: "beer"

};This looks remarkably similar to the first-create-a-constructor-then-attach-stuff-to-the-prototype dance that the class syntax is meant to abstract away in the first place! And which Douglas Crockford referred to as having stuff dangling out of the pants. It sure aint pretty.

So why is propTypes and defaultProps not part of the class definition? It is because with the current setup,

So again a compromise for the sake of a small, potential performance gain.

Yes, sure, learning what goes where in the class definition is easy enough. But I don't want to have to learn it at all!

Also: class definitions are to objects what arguments objects are to arrays - they sort of look the same, but lack much of the power and flexibility. And while employing advanced gymnastics on the definition object fed to React.createClass isn't something you'd normally do, why give up the power to be able to?

5) Dealing with super

If we're using a constructor in our component - and we very likely need to unless the component is stupidly simple (at which point it's probably better off as a pure function) - then we must remember to call super, like a well-behaved dog.

constructor(){

super();

this.state = {beer: 3};

}The super call invokes the same function in the parent class, in this case the constructor of React.Component. Failure to invoke super in a child constructor throws an error, so if you forget then everything will come crashing down.

At this point you might wonder - why isn't super called automatically? The answer is that it might matter exactly where in the constructor we make that call, so any autocalling mechanism would be inherently limiting to the class syntax.

Which makes sense but also sucks a bit, because in most cases it doesn't matter where the call is made. In general people tend to just stick the super call up top - in fact this is so common that there's even a linting rule not to reference this before calling super, to be entirely sure that your manipulations aren't garbled by the parent.

To complicate matters further we might have to demean ourselves further by passing along props and context, if we want these to be available on this inside the constructor.

All this adds up to a very raw feel - exactly the kind of stuff you'd expect to deal with when not using a library.

Wrapping up

While I don't feel particularly strongly about any of the points made above, together they make me vastly prefer React.createClass over ES6 classes. Maybe there'll come a day when I'm forced to adopt classes because the performance gain is significant, but I have yet to live it. Until then, I'll keep using React.createClass when given a choice.

Dan Abramov, not particularly fond of either syntax, wrote that

I disagree, and besides, objects are standardized too! :)

If we absolutely must use classes, then I find Angular 2's model of utilising decorators instead of inheritance to feel much nicer.

Of course it is always preferrable not to have complex components at all, and instead be able to express them as simple functions! Every instance where you're unable to make the component pure should feel like a battle lost.

PS

By using Recompose we can turn some of those lost battles into wins, for example by turning this...

let Clicker = React.createClass({

getInitialState: () => ({count: 3}),

more () {

this.setState({count: this.state.count + 1})

},

render () {

return <div>

<p>{this.state.count} bottles of beer on the wall</p>

<button onClick={this.more}>Buy more</button>

</div>

}

})...into this:

const enhance = withState('count', 'more', 3)

const Clicker = Recompose.enhance(({count, more}) => (

<div>

<p>{count} bottles of beer on the wall</p>

<button onClick={() => more(n => n + 1)}>Buy more</button>

</div>

))But in general I find that the lost readability is too high a price to pay. Even though you do get used to the pattern soon enough, it just isn't worth the gripe from your coworkers and your future self. Although you do feel clever writing the code!