Rewhat?

At its heart, Reflux is really just a PubSub library. That is, we have a Publisher API for objects who transmit events, and a Subscriber API for objects who want to listen to such events.

There is however a paradigm shift in how Reflux expects you to structure your data flow, which can be hard to grasp initially. This post will try to explain this approach.

The regular pubsub approach

For a look at what a pubsub API normally looks like let's take a look at Backbone, which has a very traditional implementation in its Events module. This module contains both publisher and subscriber functionality and is mixed in to all Views, Models and Controllers, as well as into the Backbone object itself.

The main subscriber method is listenTo:

subscriber.listenTo(publisher,eventname,callback);The publishers then have a corresponding trigger method. So if the publisher above did this:

publisher.trigger(eventname,data1,data2);Then this call would be made in response:

callback(data1,data2);You could say that each publisher is a radio transmitter with different frequency channels. A subscriber then chooses which channel (eventname) to listen to.

We have a very similar situation in the DOM, where each DOM node can transmit a range of different events.

The Reflux pubsub approach

The only thing Reflux does differently is that it does away with the different channels. Hence there is no eventname concept in Reflux. The above sequence in Reflux would be:

// first

subscriber.listenTo(publisher,callback);

// later

publisher.trigger(data1,data2);

// immediately following that

callback(data1,data2);Each publisher will only ever transmit the same kind of event. Initially I thought this to be extremely limiting - and it is - but as it turns out, this makes the whole application data flow much easier to reason about.

Reflux Stores and Actions

The core of Reflux is the Publisher and Subscriber (here called Listener) modules, which can be mixed in to any object (here using underscore/lodash):

var mypublisher = _.extend(mypublisherdef,Reflux.PublisherMethods);

mypublisher.trigger("i can trigger!");

var mysubscriber = _.extend(mysubscriberdef,Reflux.ListenerMethods);

mysubscriber.listenTo(mypublisher,callback);

var mypubsuber = _.extend(mypubsubdef,Reflux.PublisherMethods,Reflux.ListenerMethods);

mypubsuber.trigger("i can trigger too!");

mypubsuber.listenTo(mypublisher,callback);What then are the Action and Store concepts in Reflux? Well: a Reflux Action is merely an object consuming the PublisherMethods like mypublisher above, but with a few conveinence extras. Foremost is the fact that the action is a function wired to the trigger method:

var mypublisher = Reflux.createAction();

mypublisher("i can trigger!");A Reflux Store corresponds to mypubsuber, i.e. it is both a Publisher and a Subscriber:

var mypubsuber = Reflux.createStore(mypubsubdef);

mypubsuber.trigger("i can trigger too!");

mypubsuber.listenTo(mypublisher,callback);What about an equivalent for mysubscriber? Well - as we will see, an object which does nothing but listen in your app will likely be a view. For React, Reflux therefore supplies a special mixin containing the ListenerMethods and which takes care of mopping up if the view goes out of existence:

var mysubscriber = React.createClass({

mixins: [Reflux.ListenerMixin],

// other stuff from mysubscriberdef

});

mysubscriber.listenTo(mypublisher,callback);Communicating between objects

Now that we know what tools Reflux supplies, we can start to discuss how to use them! First consider the problem; Something is happening in one object (a user event caught in a view), which we want to react to somewhere else (say a localStorage module storing the setting that the user just selected). How can we set this up?

For discussion's sake, let's explore a few different ways in which this could be set up in a Backbone app:

Take 1 - direct calling

The view can have a reference to the settings module and call a method on it directly:

var settings = require("./settings");

var settingview = Backbone.View.extend({

events: "click .submit":"toggleSetting",

toggleSetting: function(){

settings.updateVolumeSetting(this.$el.find(".myinput").val());

},

render: function(){ /* stuff */ }

});

Simple but a bit clunky. The view needs a reference to the settings object, and it is dependant on the exact API of the settings.updateVolumeSetting method. The two objects are very tightly coupled, which is a good way to ensure future headache.

Take 2 - object-triggered event

The settings module can listen to events from the view:

// settingsview.js

var settingview = Backbone.View.extend({

toggleSetting: function(){

this.trigger("changedvolume",this.$el.find(".myinput").val())

},

// rest like before

});

// settings.js

var settingsview = require('./settingsview');

var settingsobject = Backbone.Model.extend({

initialize: function(o){

this.listenTo(settingsview,"changedvolume",this.updateVolumeSetting);

},

updateVolumeSetting(val){ /* store new volume value if it's metal enough */ }

});Now we must instead pass the view to the settings object, which isn't much better. At least we got rid of the API dependency, but the coupling is still tight.

Note that this approach also requires that the settingsview.js returns a view instance and not a constructor.

Take 3 - using a global event bus

We can use a global event bus to transmit the events. In Backbone, the Backbone object itself is a convenient place for this at it is already a dependency of all objects, and it contains the Events API.

// settingsview.js

var settingview = Backbone.View.extend({

toggleSetting: function(){

Backbone.trigger("changedvolume",this.$el.find(".myinput").val())

},

// rest like before

});

// settings.js

var settingsobject = Backbone.Model.extend({

initialize: function(o){

this.listenTo(Backbone,"changedvolume",this.updateVolumeSetting);

},

// rest like before

});This looks a lot better - we no longer have to pass object references around at all! Instead of having one of the participating objects depend on the other, we make them both depend on a third party (the Backbone object) which takes care of the communication.

On the other hand, communicating lots of events over a central channel like this can easily get out of hand; let your guard down for an afternoon of coding, and you'll suddenly have a real hell trying to figure out who transmitted what to make the app blow up in your face like it just did.

Take 4 - Using Reflux

Here's what a solution could look like using Reflux in our Backbone example (not an advocated match, but used here for the sake of discussion (and I'm not even sure importing Reflux in this way would overwrite Backbone's Events API (probably not))):

// actions.js

var actions = Reflux.createActions(["changevolume", /* likely some other actions too */ ]);

// settingsview.js

var actions = require("./actions");

var settingview = Backbone.View.extend({

toggleSetting: function(){

actions.changevolume(this.$el.find(".myinput").val())

},

// rest like before

},Reflux.PublisherMethods);

// settings.js

var actions = require("./actions");

var settingsobject = Backbone.Model.extend({

initialize: function(o){

this.listenTo(actions.changevolume,this.changevolume);

},

// rest like before

},Reflux.ListenerMethods);As you can see, Reflux is really similar to the global event bus solution from before. The only difference is that instead of one global channel in which we specify event type, there are lots of global channels, each dedicated to a specific event.

Global event busing the Reflux way

So, is having many global channels really any better than having just one? As it turns out, yes! There are several advantages:

- No more magic string event names like

changedvolumejust begging to be misspelled (granted we could mitigate that risk with a constants object, but that is a hassle too). - Code becomes slightly shorter, less verbose and easier to read

- The file

actions.jswill in essence become a list of all available events in your app! This is helpful in many ways, perhaps foremost that it forces you to think about your events on a higher level. - It also becomes very easy to compartmentalise the events if you want to. Instead of a single

actionsdefinition you can split it into thematically defined modules;useractions,serveractions, etc.

A comparison with Flux

On a higher level, the structure employed by Flux and Reflux are very similar. Flux too employs a global event bus approach, with event-specific channels. However, instead of making all actions into event dispatchers like Reflux, Flux employs a single "app dispatcher" much like Backbone, although with mechanisms in play to enforce the event-specific channel approach.

The fact that Flux has a central Dispatcher makes for lots of cruft in the code, as our previous code comparison between the two clearly demonstrated.

If you need more convincing, compare the Reflux TodoMVC implementation with the Flux version.

Using Reflux in React

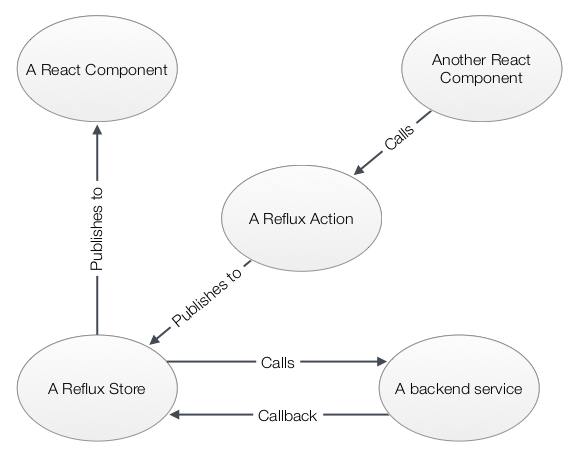

Enough Backbone babbling, what about best practices for using Reflux in React? We touched on it in the previous post, but wanted to revisit that here in the context of event flow. Here therefore is a stone tablet of divine law:

- Isolate database communication into Stores.

- When a Store receives new data from the server, it should trigger with the new data.

- React components should listen to the relevant stores.

- React components should call actions in response to user events.

- Stores should listen to actions and potentially talk to backend API:s accordingly, which might in turn cause new data to be sent back and thus an event to be triggered.

To wit:

- A component calls Actions and listens to Stores.

- A store listens to Actions and triggers events.

A chat example

It's been done to death, but here is the (relevant parts of a) Firebase chat setup from a recent site work of ours:

// A view displaying the list of chat messages. Listens to changes from the Chatstore

var Chatlog = React.createClass({

mixins: [Reflux.connect(Chatstore,"messages")], // will set up listenTo call and then do this.setState("messages",data)

getInitialState: function(){return {messages:{}};},

render: function(){

return (

<div>

<Chatform />

<div>

{_.map(this.state.messages,function(msg){

return (<p><small>{msg.date}</small><span>{msg.message}</span>);

})}

</div>

</div>

);

}

});

// a view displaying the form for entering a new msg. calls addmsg action

var Chatform = React.createClass({

onSubmit: function(e){

actions.addchatmessage(this.refs['field'].getDOMNode().value)

e.preventDefault();

return false;

},

render: function() {

return (

<form onSubmit={this.onSubmit}>

<input className='form-control' type='text' ref='field'/>

<button className='btn btn-default' type='submit'>Send!</button>

</form>

);

}

});

// A store listening to addmsg action. Will trigger upon receiving server data

var chatRef = new Firebase("https://<firebaseusername>.firebaseio.com/web/data/chat");

var Chatstore = Reflux.createStore({

init: function(){

chatRef.on("value",this.updateChat.bind(this));

this.listenTo(actions.addchatmessage,this.addChatMsg.bind(this));

},

addChatMsg: function(msg){

chatRef.push(msg,function(err){

if (err){

actions.error("Chat send failure: "+err);

} else {

actions.log("Message sent",msg);

}

});

},

updateChat: function(snapshot){

this.trigger((this.last = snapshot.val()||{}));

},

getDefaultData: function(){

return this.last || {};

}

});Here's what will happen when a user enters a new chat message:

- The Chatform React component will call the

addchatmessageReflux action - Chatstore is listening to that action, and will make an API call to Firebase in the

addChatMsgmethod - Firebase will update its data

- Chatstore receives the new data from Firebase in the

updateChatmethod, which makes the store trigger an event with the new data - Chatlog is listening to the store and so receives the new data, which updates its state and causes a render

If we anonymize the components to get back to the stone tablet laws, here's what's going on:

Each "published to"-arrow of course corresponds to a reversed "listens to"-arrow.

Wrapping up

This post aimed at...

- explaining how Reflux is merely a pubsub solution minus the event names,

- advocating why this is a good idea,

- ...and show how to utilize this flow in React.

If any of these three points missed their mark, scroll back to the top and read again, or make an angry comment below!